Submodule 11D

Learning Goals:

Solid Waste

Let us start with a great presentation by the Alaska DEC. This is a PowerPoint with audio that resides on the UAF site Kaltura. It is a very large file, but should stream so you don't need to download it. But all you should need to do is click on the link here. LINK. https://media.uaf.edu/media/t/0_hfxwdqy4

Next, we'll overview some more solid waste concepts.

Note we might define MSW as “household trash,” what you and I put into the plastic garbage bags and take to the transfer site (we don’t have local trash collection in my neighborhood – rather we take or trash to dumpsters at a “transfer site.”) By that definition, MSW excludes “special” materials, such as construction debris, lawn clippings and leaves, sludge from wastewater treatment, and agricultural and industrial waste, as well as junk appliances and vehicles. These “special” solid wastes are “non-hazardous,” but almost always have special procedures and often fees associated with disposing of them. However, once the wastes are at the landfill, they are treated about the same as MSW. Thus, we might or might not include special wastes in the term “MSW.” Some authors distinguish wastes such as ash from power plants that are not usually the responsibility of a municipality.

Here’s a slightly deeper take on that, skip 7:38 to 12:39 if you wish, but do look at the “economics” at the end. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s5jKL1OxbcE&list=PLiNgTF1S32SiJQNxZiZFrLk9iUI4ij5ww .Some of you know, I also teach engineering economics, where we do cost-benefit analysis in some depth. But I avoid, insofar as practical, the notion of “externalities.” The reason is that once you get beyond the dollars and cents you pay or do not pay, there is no limit to what is external to the matter you are considering – there is a whole universe that is “external” to the contract or item we are considering. Nonetheless, for many matters regarding MSW disposal, engineering takes a back seat to the externalities of the situation.

A little more depth and some fun with history and geography:

Before we get into the disposal of hazardous waste, we need to have a discussion of SOLID WASTE. Let’s break those two terms down. First, a “waste” is any material that is rejected for further use – it is now or shortly will be “discarded.” The term “solid” is interesting. While wastewater has been the bread and butter of environmental engineers for about 3000 years, solid waste is a much more recent concern. Until recently, in most of the non-industrial world, there was little solid waste. Waste was recycled or scavenged or readily bio-degradable. I worked in a semi-rural area in Nigeria where we had a contractor that came into our compound once a week and emptied our refuse cans into a barrel he had on a cart. As he left the compound he had a swatter that he used to shoo kids away from the barrel. I followed him one day. After he put some distance between him and compound, he lost interest in the kids, who quickly got into the trash. Our discarded cassette tapes became toys, edible items got eaten, bottles and rags were scooped up. A short distance away was a vacant lot, where our contractor dumped what was left from the barrel on the ground. By then there was little left, but passer-byes quickly picked up what was left. Surveying the lot, that must have had several years of trash from our compound, I could not’t identify anything of note. Most of the remainder piles were overgrown with plants.

Not too far away, there was the butcher section of the market. Here animals, mostly goats, were led into the area, the animals killed and their carcasses butchered. The meat simply hung out for sale. But the offal – the contents of the goat? That was dragged to one end of the market where fleets of vultures scooped the material up and just ate it in place. The vultures were protected by custom. Also, the vultures knew they were allowed to eat the offal, but not the hanging meat. It turns out that is not that uncommon. Here is a story about that kind of solid waste in Charleston, South Carolina.

https://charlestontimemachine.org/2017/07/28/the-rise-of-the-urban-vultures/ BTW, that may be the origin of the tradition (and state law) not to kill ravens in Alaska – they serve the same function, cleaning up animal debris.

While offal was always obnoxious, if not a known health hazard, other wastes were not so. Paper was rare, glass was recycled. Leather and cloth was recycled and bio-degradable. Urban area did have ashes and the industrial revolution added metals and such. In 1864 Charles Dickens has a character in Our Mutual Friend, Nicodemus (Noddy) Boffin, the Golden Dustman, who collected garbage (sorry, that is “solid waste”) and he and his benefactor make a fortune from collecting and sifting through the “dust.”

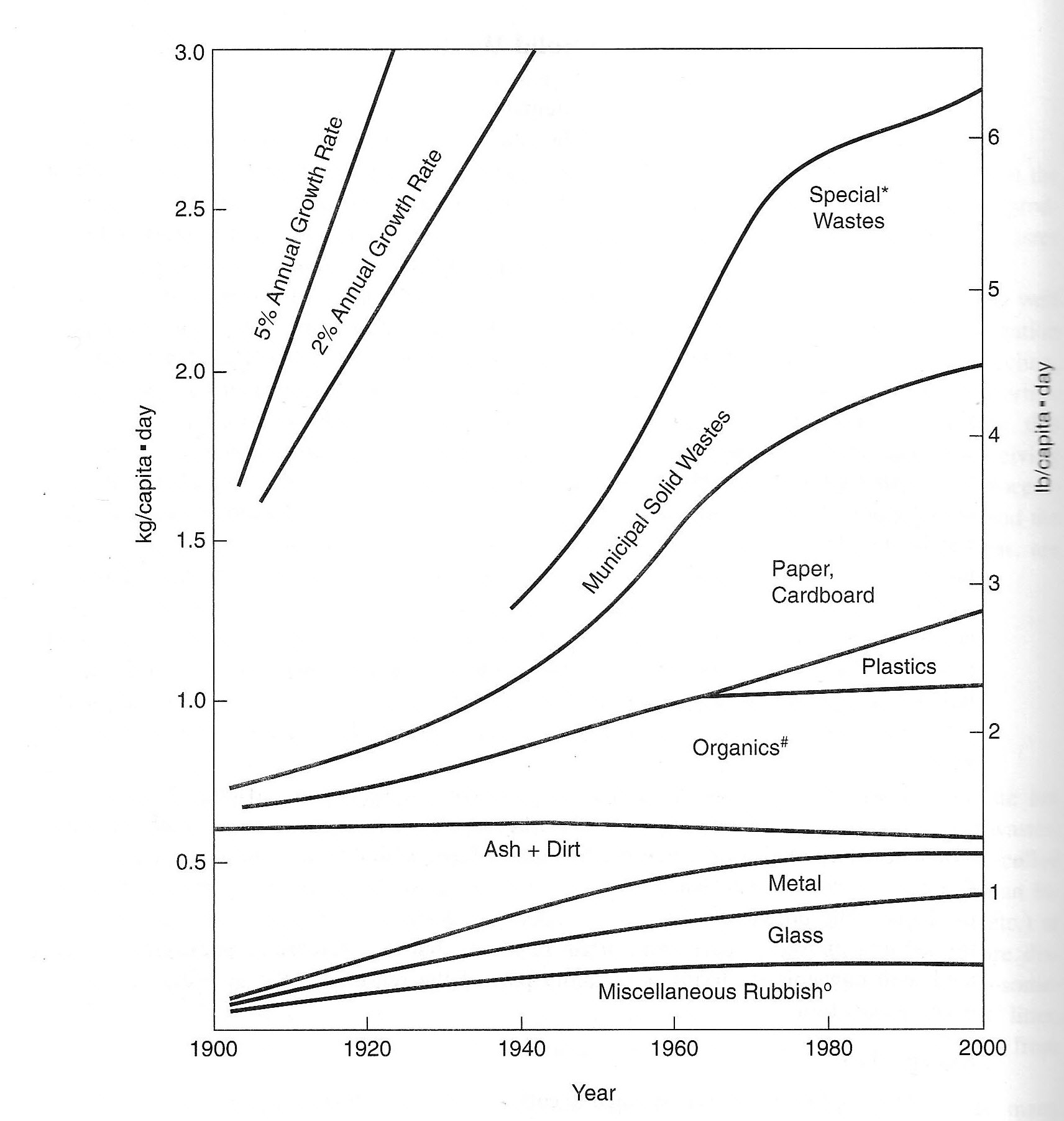

But with prosperity and urbanization in the 20th Century, the amount of solid waste increased

test top test bottom

(From Henry and Heinke) Note the right hand axis is pound per person per day. The MSW line is the total. See that Ash and Dirt decline due to the change in home heating from wood and coal to oil, gas, and electricity.

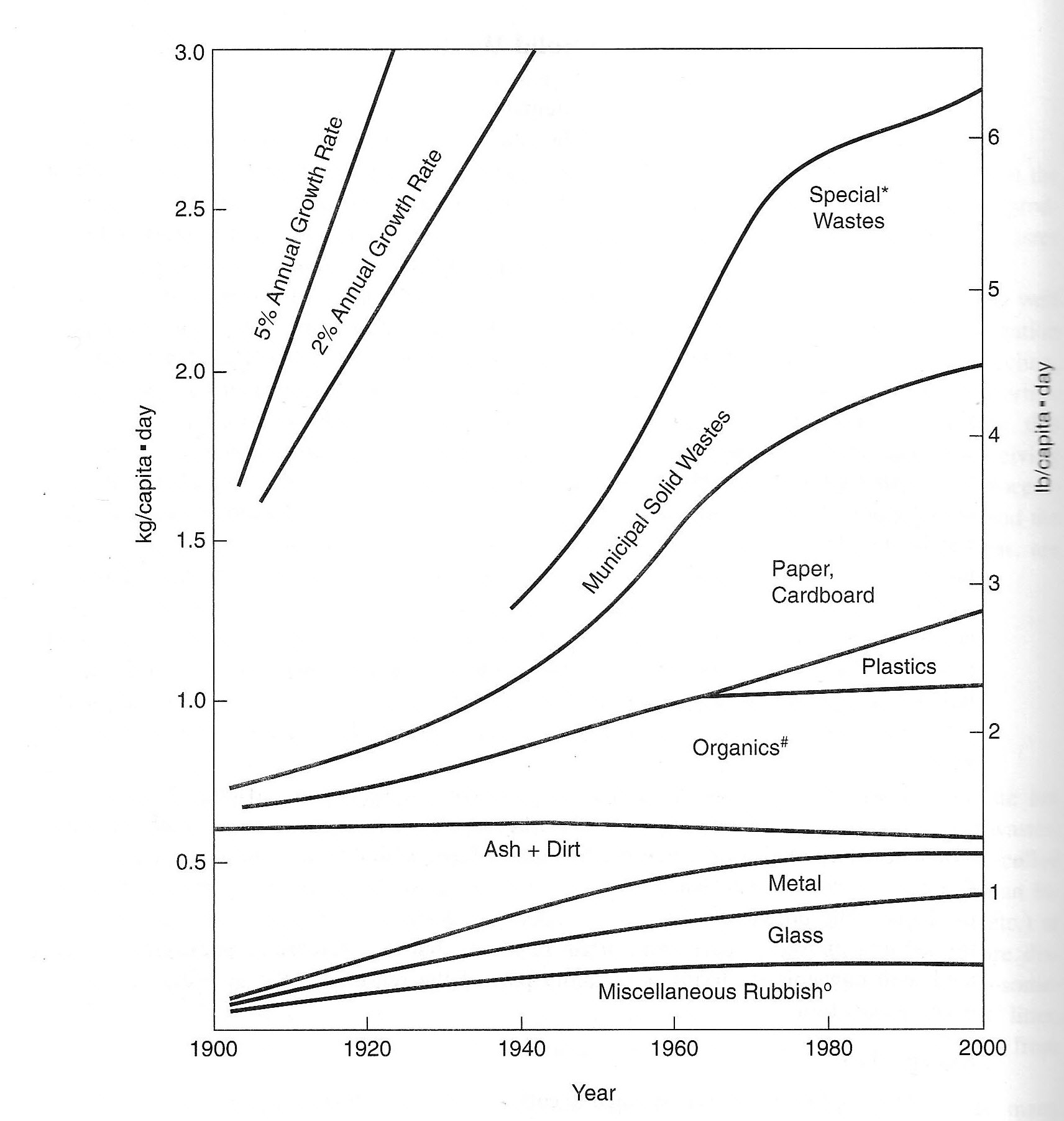

Below we see that the per capital generation of MSW has declined since 1990, while the total has increased, probably with population increase. The EPA that generated the report states this is due to recycling.

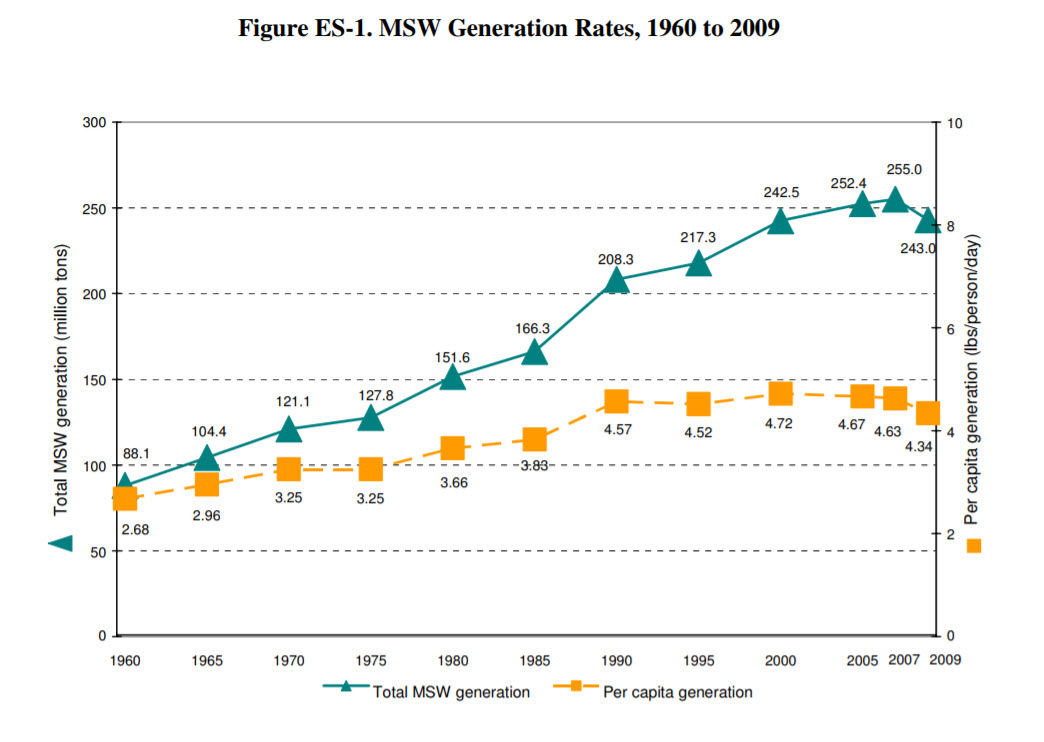

(Both from MUNICIPAL SOLID WASTE IN THE UNITED STATES: 2009 FACTS AND FIGURES, EPA

From https://archive.epa.gov/epawaste/nonhaz/municipal/web/pdf/msw2009rpt.pdf

Here’s what is in the MSW before recycling. Data is from 2009. Note this definition of MSW excludes special wastes of ash and agricultural wastes. Note that data is presented often presented by weight. In many regions, the amount of rainfall may greatly affect the weight of the waste.

How about recycling? We must be careful, lest we meet the fate of so many heretics.

And get burned at the stake – incineration below – but in Course Documents folder, in the Special Documents folder is a very heretical work from the New York Times – not the usual abode of un-green heresy. Please read The Reign of Recycling and get ready to answer a heretical question based on that article.

Between different regions and seasons, waste may vary by composition, density, and energy content (combustibility). Economics and social customs might very considerably. Use of home garbage grinders also affects the amount of garbage.

Before we entomb our MSW in a landfill, we need to get it from under my kitchen counter. We won’t get too much into details on collection and transport, but note that it can be a complex, multi-stage process, especially if the landfill is far from the urban center. Waste is often compacted in several stages and then fit into long-haul truck or rail cars. The intermediate transfer step often takes place at a “transfer station.” In most cities where there is regular trash collection, sanitation workers empty individual trash containers into a “packer truck,” which goes to a transfer station to be compacted further.

As noted in the YouTube, the EPA has a hierarchy of MSW disposal alternatives.

“Waste-to-energy” is a term that sounds much better (greener) than “incineration.” Waste-to-energy implies the energy produced by incineration is converted to some useful form – typically electricity. Without the waste-to-energy, there is usually a benefit from volume reduction – the ash is only about 10% the volume of the original MSW, so a landfill might last much longer. Also, burning keeps some vermin down, which is not huge a problem at a well-manged landfill, but might be at a smaller, less well managed facility. Also, compared with waste-to-energy, an incineration facility is much less expensive and requires less maintenance or skilled labor. Although the burning does produce carbon dioxide, theoretically it about the same as will be generated in the landfill as the waste decomposes, and the burning will not produce methane.

The next is from a website of a company that supplies waste-to-energy systems, quoting the EPA without citations:

Waste-to-energy has earned distinction through the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s solid waste management hierarchy, which recognizes combustion with energy recovery (as they refer to waste-to-energy) as preferable to land filling. EPA recommends that after efforts are made to reduce, reuse, and recycle, waste should be sent to waste-to-energy plants where the volume of trash will be reduced by 90%, the energy content of the waste will be recovered, and clean renewable electricity will be generated. EPA’s hierarchy reflects what EPA has stated previously—that the nation’s waste-to-energy plants produce electricity with “less environmental impact than almost any other source of electricity.”

Municipal solid waste must be managed using an integrated waste management system. IWSA encourages and supports community programs to reduce, reuse, recycle and compost waste. Communities that utilize waste-to-energy plants recycle nearly twenty percent more than communities that do not have waste-to-energy plants. In addition, the nation’s waste-to-energy plants recycle more than 700,000 tons of ferrous metals per year—enough to manufacture more than a half million new cars.

However, after waste is reduced, reused, and recycled, waste will be leftover that must be managed. That is where waste-to-energy comes in. EPA's solid waste hierarchy gives preference to waste-to-energy over landfills because waste-to-energy reduces the volume of waste by 90 percent, destroys bacteria and pollutants, prevents methane from being created, saves valuable land, recovers more energy from waste, and creates a more sustainable municipal waste management system.

It is very difficult to site new incinerators or waste-to-energy facilities. NIMBY – not in my backyard – will drive the local political process, even if state or federal policies encourage new facilities. Today, stack gases are strictly regulated, but some facilities indeed smell. Also, the facility will be an industrial facility with large trucks coming and going.

Landfills

Please scan this EPA site:

https://www.epa.gov/landfills/municipal-solid-waste-landfills

https://www.epa.gov/landfills/basic-information-about-landfills#whattypes

Note the distinction between RCRA Subtitle C, which is for hazardous waste and RCRA Subtitle D, which is for non-hazardous waste. RCRA Subtitle D is, for most practical matters, administered by the states. The regulations are quite broad and states (quite properly) have a lot of discretion in applying them. [An ardent constitutionalist might note that there is a substantial federal issue in hazardous waste, since it was often transported across state lines and to and from foreign countries. On the other hand, after ocean dumping of MSW was banned, there is no federal issue in MSW. ]

Then click here regarding MSWLF, https://www.epa.gov/landfills/municipal-solid-waste-landfills read the first two units and glance at “regulations” to note the complexity.

Here are the major criteria:

Click on the links for groundwater monitoring, closure and post-closure care requirements, and financial assurance. Get a handle on what those terms mean.

Before we go to Alaska, here’s a fun video. It is made by a company that builds and maintains landfills. It has some neat graphics, photos and takes on phytoremediation and some clever use of animals. Note which animals.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=821RZegnHdM

The Alaska regulations for solid waste are found in 18 ACC 60, for which a link is found on the bottom of this page. http://dec.alaska.gov/eh/sw/index.htm

Alaska is different? No, Alaska has regulations more or less the same as other states regarding MSW landfills. Other than having some special notations about permafrost. However, Alaska has many “bush” communities – rural communities. Not on a road system and transportation very limited much of the year, these small communities often have scant resources. In addition, they are not municipal corporations able to tax property. They provide common services by a variety of fees and revenues sources, such as proceeds from Bingo games. Some have limited services provided by village corporations or tribal entities – but never very much. On the other hand, regarding solid waste, these small villages do not contribute much. Thus Alaska has a special set of regulations, Category III, that reduce the burden of landfill maintenance and administration.

DEC has a page especially for rural solid waste that features some highly qualified people: http://dec.alaska.gov/eh/sw/rural-ak.htm

For some insight into the scope, that website has a link to a table that assigns one of the four DEC specialist to each village. http://dec.alaska.gov/eh/sw/class-3-table.html . Did you know there were that many villages? For some practical demographics, I went to the font-of-all-knowledge, Wikipedia, and looked up the village of Nightmute (about which a movie was made). It has a population of 280, with a median household income of $36,000. Realize that these villages are often a hundred miles from the next village. So, as a practical matter, most of these villages do not have a permitted solid waste landfill at all. Waste is just burned or brought, by snow machine or four-wheeler, to a location near the village and dumped. If the village has the wherewithal to permit a landfill, however, they may be able to get some federal funding for some basic maintenance.

Let’s wind up with miscellaneous items.

Household hazardous waste. EPA has a good discussion: https://www.epa.gov/hw/household-hazardous-waste-hhw Many of the items in our homes are indeed hazardous, but we toss them in the trash with our Big Mac wrappers. Hazardous as they are, they are not regulated by RCRA Subtitle C so we don’t need a permit to trash our oven cleaner. However most local landfills have programs to separate HHW from MSW.

Monofills. We’ll wind up by pointing out there are specialized landfills for special wastes. “Monofills” is the term for a landfill that has only one type of material, for example, drilling muds or construction debris. For these special permits are issued consistent with their contents. None of these wastes are hazardous within the mean of RCRA, but having a special permit and special landfill location is often more efficient for the industry and the regulator.